Yasmine Nasser Diaz is a multidisciplinary artist whose practice navigates overlapping tensions around religion, gender, and third-culture identity. Her recent work includes immersive installation, fiber etching, and mixed media collage using personal archives and found imagery.

For more information, please see: yasminediaz.com, and on Instagram @yasmine.diaz.

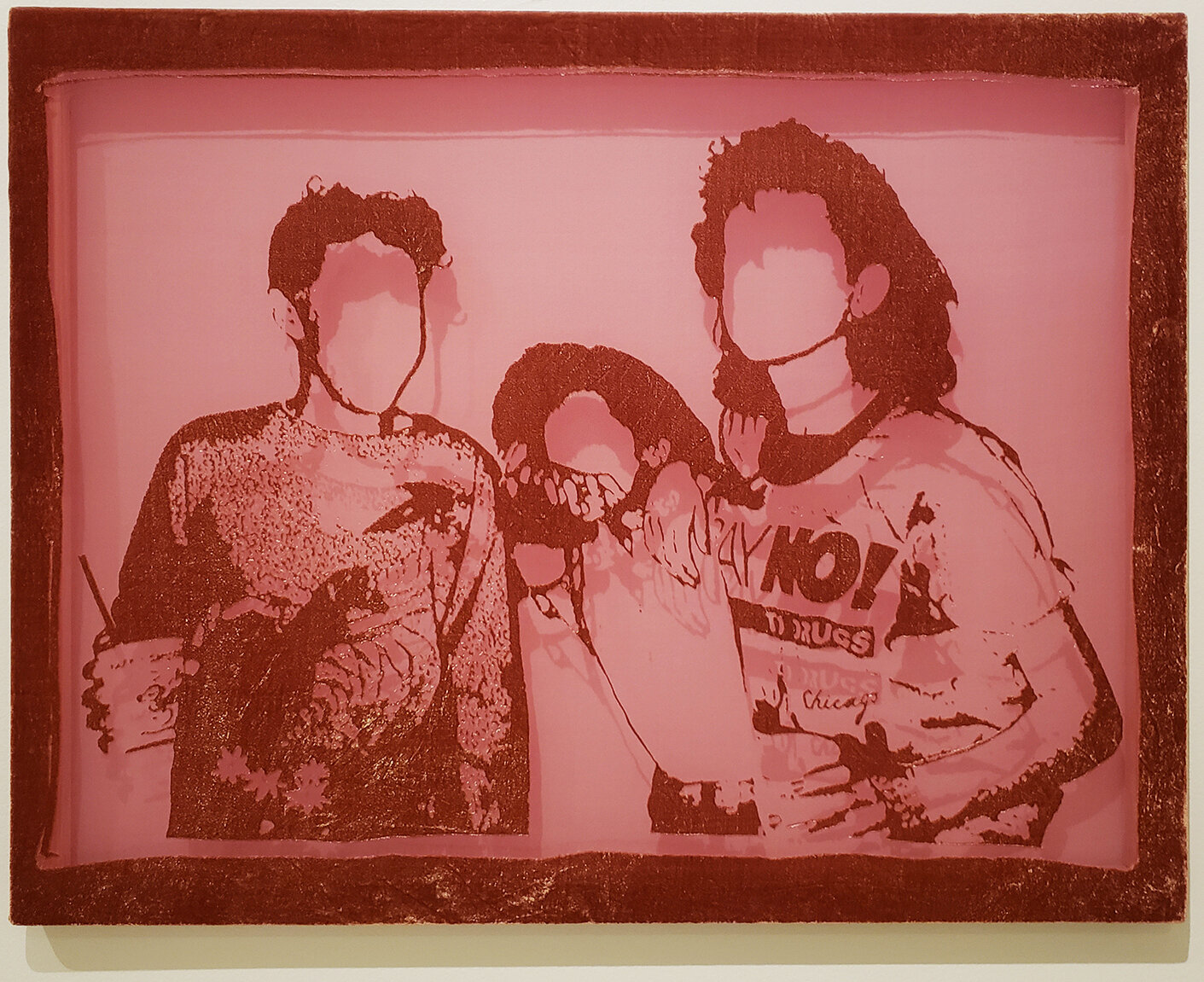

Yasmine Nasser Diaz, Say No To Drugs, 2020. Silk-rayon fiber etching. Image courtesy of the artist.

It's my experience that most artists engage with some level of self-isolation in their day to day art practice. Has this been your experience? And if so, have you found these innate rhythms to be helpful during this larger, world-wide experience of isolation?

Pre-pandemic, I spent a lot of time alone in my studio so I wasn’t panicking about sheltering in place at first. But after a while, the loss of social gatherings began to add up and made me feel off balance. Now I’m very much preoccupied with everything that’s happening and this revolutionary moment. It’s exhilarating and I feel a kind of hope for the future of this country that I’ve honestly never felt before. It’s also been very draining at times, consuming so much information at once. I’m trying to return to some balance while staying informed, active, and continuing to help shift things forward, in my own small ways.

It would be great if you could briefly talk us through your practice. Understanding it is integral to appreciating the multivalence of your work.

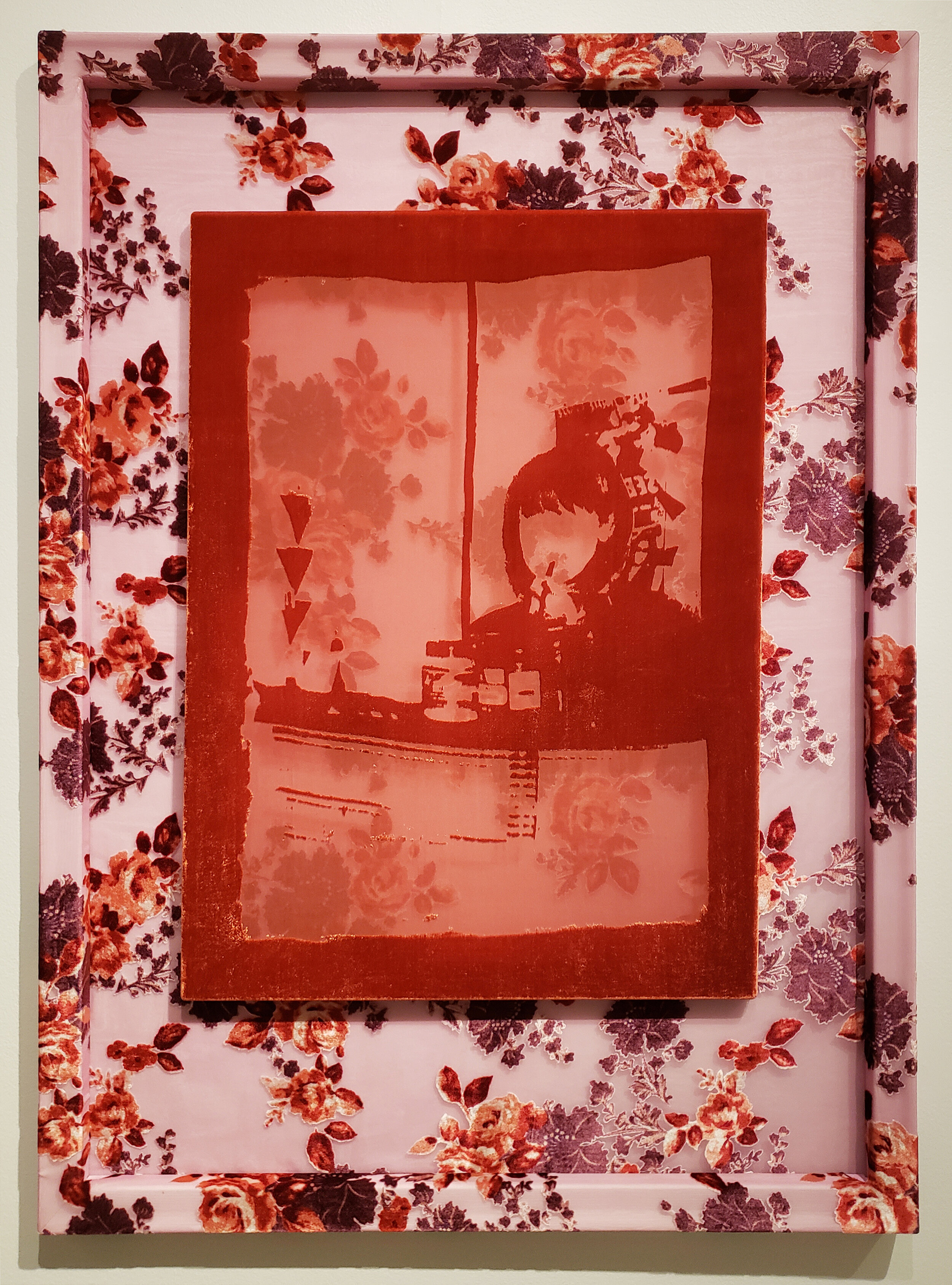

My main bodies of work stem from the use of mostly personal photography and collage. I even think of my installations as a form of collage work and my recent fiber etchings as translations of photographic images. I currently have a solo exhibit at the Arab American National Museum in Dearborn that incorporates all of these elements -- it’s been installed since March but has yet had a chance to open to the public. In the months before the show, I taught myself the process of fiber etching (also known as burnout fabric). I had been incorporating imagery of textiles more in my collages and actual fabric pieces in my assemblages when I came across some old photos of family members wearing burnout fabrics. One of my fellow residents at the Vermont Studio Center last summer was a fiber artist, Mia Weiner, and she generously let me pick her brain about etching fabric. It was a pain to get past the learning curve but I was determined to get it right and I’m glad to have stuck it out. There are so many layers to why the material resonates -- burnout was popular in the 90s when I was growing up and it's also the time period this work focuses on. It was also used often to make a Yemeni style of dress called a dir’ which some say is only to be worn by married or engaged women. My exhibition, soft powers, centers adolescence and more specifically, Yemeni-American girlhood. It hit a lot of marks for me.

Yasmine Nasser Diaz, Noxzema and Lipliner, 2020. Silk-rayon fiber etching. Image courtesy of the artist.

Has any of your imagery shifted in a reflection to what's currently happening? And why, or why not?

Not exactly. I tend to be a slow processor and I don’t feel anywhere near ready to respond to this moment in my work. However, I did return to a series that brings me some solace. It’s very different from the rest of my work and uses imagery mainly of desert plants. I have a loose sci-fi narrative developing in my head that sets the story millions of years in the future. This is going to sound dismal but it speaks to how humanity has contributed to the ecological decline of the planet. In my opinion, it has a hopeful outcome because the plants evolve to essentially takeover before we completely destroy everything.

Yasmine Nasser Diaz,Thick as Thieves, 2020. Silk-rayon fiber etching. Image courtesy of the artist.

What is bringing you solace, or even joy, in this moment?

When the period of sheltering in place began, I was worried that we wouldn’t come out of this learning what we should. That we wouldn’t appreciate the importance of taking care of each other through more collective actions. But as the confinement continued followed by the protests and uprisings, there’s been a radical shift. Even though the momentum has simmered in some ways, I think we are forever changed. We’re witnessing conversations happening and resources being shared on an unprecedented level. This is all possible because of the people that have been doing this work for years -- around racial justice, prison abolition, criminal justice reform, radical re-education of this country’s history, etc. The groundwork has been laid but now, people are listening. This gives me a lot of hope.

Yasmine Nasser Diaz, Truth or Dare, 2020. Silk-rayon fiber etching. Image courtesy of the artist.

Are you reading anything?

We Are Never Meeting in Real Life by Samantha Irby and How to be an Anti-Racist by Ibram X. Kendi -- two very different books but I recommend them both!