Johannah Herr’s studio practice conceptually centers around investigations of State violence. Herr thinks that the State is “an apparatus that holds a unique capacity to create violence, exclusion, and exploitation— acts often condoned by its own citizens (provided that the aforementioned violences are enacted against ‘others’). I am therefore also interesting in the roll that ideology, consumerism and privilege play in distracting some people from violences that are deeply felt by others.”

“While my work largely deals with (United States of) American State-sanctioned violence, the genesis for my interest in these conceptual issues began with my anti-trafficking work in Thailand. In 2011 I co-founded an anti-human trafficking, women’s empowerment NGO that works to empower ethnic minorities and Burmese refugees in Thailand. While this project is distinct from my artistic practice, it has deeply affected how and why I choose to make art. Working with undocumented refugees fleeing genocide in Burma exposed me to the extreme precarity and marginalization created by abusive military and bureaucratic policies. While I am fortunate enough to be a natural born US citizen (thus sheltered from legal-status marginality in my own country), my work in Thailand allowed me to recognize the structural exploitations within the US and Thailand as functioning largely the same. It therefore became my goal within my art work to expose these structures of exploitation within a US context such that the viewer is forced to reconcile with this content.”

Herr holds an MFA in Sculpture from Cranbrook Academy of Art (2016) and a BFA from Parsons (2009). She teaches at Parsons and NYU and is the Co-Founder of the NGO Daughters Rising based in Mae Wang, Thailand.

For more information, please see: www.JohannahHerr.com, and on Instagram @johannah_herr.

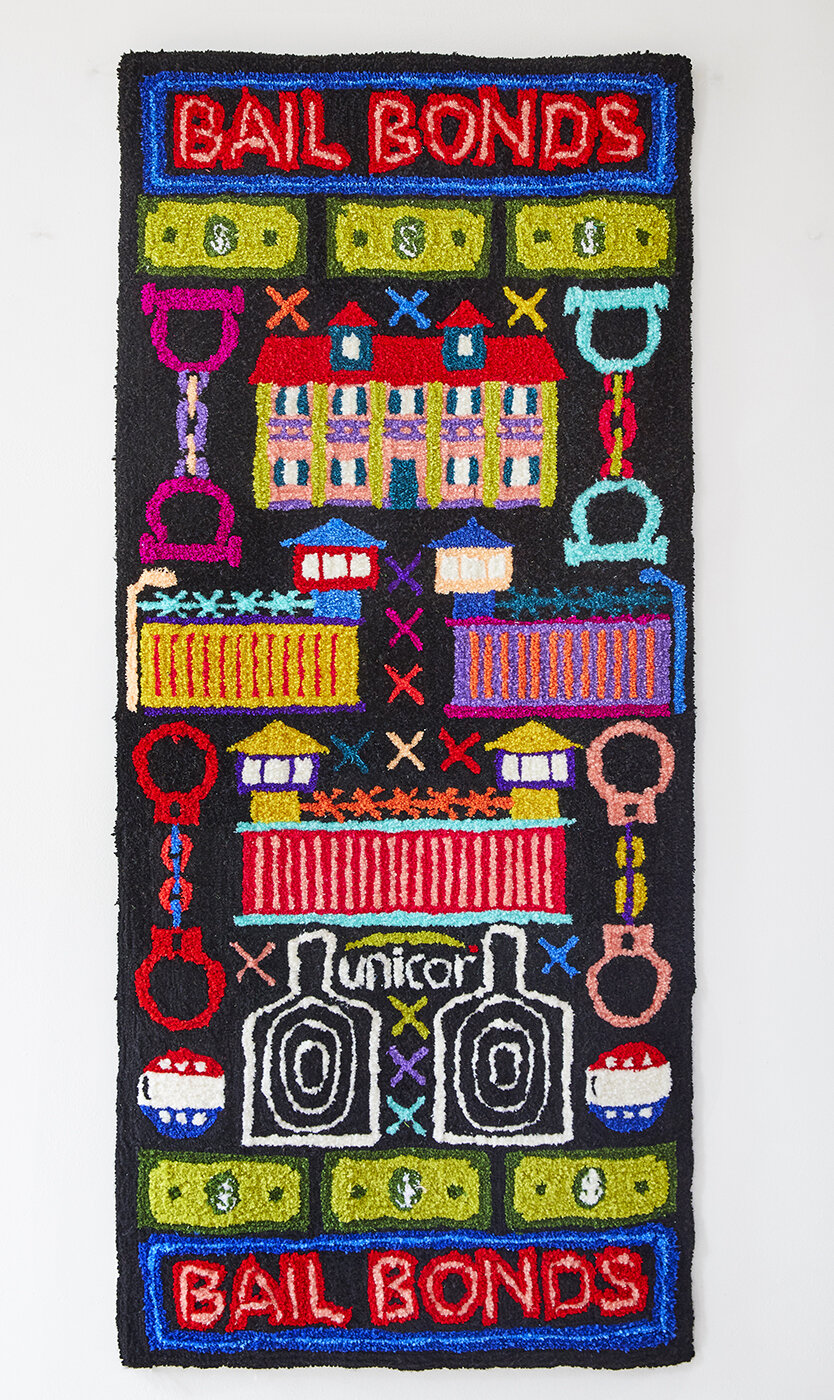

Johannah Herr, Domestic Terrorism: War Rugs from America VI (War on Drugs), 2020. Machine-tufted rugs using wool, cotton and acrylic yarn. 6' x 3' x 1". Image courtesy of the artist.

First, and most importantly, how are you doing? How are you navigating the highs and lows?

I’m OK. It’s been an intense few weeks of emotions oscillating between anger, grief, despair, hope, feeling isolated and feeling community in a way I haven’t felt in a long time. The Black Lives Matter revolution that has happened after the killing of George Floyd for me has completely overshadowed my experience of COVID and, quite frankly, my brain chatter in general. On one hand, it is super exciting— we are FINALLY talking about the injustices that have been going on since the inception of the US policing system in a real way (namely, in a massive mainstream media way in which white folks who didn’t think they had any skin in the game are being forced to recognize the brutal systemic injustice for what it is) and our government is being pressured to make real change. I’ve been to a lot of protests since everything started, and there is palpable sense of community and potential to really make a radical shift in mainstream culture that I can’t help but find inspiring. But on the other hand, this sense of connectedness is never quite eclipsed by the acute pain, grief, and violence that began this revolution in the first place and continues around us. Police killings of unarmed Black people have not stopped since Floyd’s death. Police brutality towards the BIPOC community and protesters has arguably ramped up. And we have a LONG way to go to actually dismantle systemic racism in America. But I have been feeling more hopeful than not that it’s possible. So yeah, it’s been a lot of highs and lows.

Johannah Herr, Domestic Terrorism: War Rugs from America V (Flint), 2020. Machine-tufted rugs using wool, cotton and acrylic yarn. 4' x 3' x 1". Image courtesy of the artist.

It's my experience that most artists engage with some level of self-isolation in their day to day art practice. Has this been your experience? And if so, have you found these innate rhythms to be helpful during this larger, world-wide experience of isolation?

Yes, I love to be left alone in my studio. In the beginning of COVID I had been looking at quarantine as a kind of home residency program and had secretly been really enjoying the break from attending art events (I usually go out a lot). But the protests have kind of popped my quarantine bubble so now I am just missing catching up with other artists and seeing what everyone is doing in their studios. I do think that as an artist and someone who juggles 3 careers (artist, professor and co-founder/associate director of an NGO) I am well-equipped for time management in isolation. While I admittedly have allowed myself to watch more Netflix than I ever would normally, I have been working on various projects and kept quite busy these past few months.

Johannah Herr, Domestic Terrorism: War Rugs from America IV (El Paso Shooting), 2020. Machine-tufted rugs using wool, cotton and acrylic yarn. 4' x 2.5' x 1". Image courtesy of the artist.

Johannah Herr, Domestic Terrorism: War Rugs from America Series, 2020. Machine-tufted rugs using wool, cotton and acrylic yarn. Image courtesy of the artist.

It would be great if you could briefly talk us through your practice. Understanding it is integral to appreciating the multivalence of your work.

My practice continually circles around questions of how to reckon with State violence, grievability* and ideology: What violences are we directly and tacitly responsible for as Americans? Whose deaths / suffering are considered grievable and whose are not? How does ideology distract us from understanding our role in such violence? The form of the work depends on how I want to address those questions, so my material explorations are pretty broad. I make sculptures, installations, works on paper, video work, and recently I have been making tufted rugs. As an artist and designer, there is also a through-line of commercial design sense to the work, which I use as a subconscious strategy for creating aesthetic desire — I want people to wantthe work before they necessarily understand what it’s about.

I am currently in the middle of a body of work called Domestic Terrorism: War Rugs from America for an upcoming solo show at Elijah Wheat Showroom in New York. The work comprises a series of machine-tufted rugs that use the material and visual narrative strategies found in Afghan War Rugs to interrogate State-sanctioned violence in America. [War rugs are traditional Afghan rugs that began to incorporate military weaponry into their design motifs during the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, and continue to this day (though now incorporating American drones)]. While the content of my rugs does not singularly address the ongoing war in Afghanistan, the idea of creating a war rug to acknowledge or even exorcise pervasive State violence grounds the basis of this body of work. Domestic Terrorism: War Rugs from America aim to implore viewers to intimately consider the violences— immigrant detention, mass incarceration, wars abroad, gun violence, police brutality, inadequate healthcare and income inequality amongst others— that comprise our domestic American landscape.

While no Central American immigrant needs a rug to remind them of the horrors of US immigration policy, and no African American family needs a rug to remind them of the impact of mass-incarceration on Black communities, I aim for these pieces to be a speculative proposal for an increased awareness and intimate reckoning of injustice by communities whose privilege shields them from directly experiencing such issues.

*The term grievabilty comes from Judith Butler’s text Frames of War

Johannah Herr, Domestic Terrorism: War Rugs from America II (Mass Incarceration), 2020. Machine-tufted rugs using wool, cotton and acrylic yarn. 5' x 2.5' x 1". Image courtesy of the artist.

Johannah Herr, Domestic Terrorism: War Rugs from America Series, 2020. Machine-tufted rugs using wool, cotton and acrylic yarn. Image courtesy of the artist.

Has any of your imagery shifted in a reflection to what's currently happening? And why, or why not?

As someone whose practice revolves around critiques of State violence my work is already exactly about what is currently happening. So, I was actually making rugs about police brutality, mass incarceration and biased policing anyway right around the time that George Floyd was murdered. However, the protests have temporarily changed my thoughts on sharing the work. As a white ally, I have been thinking a lot about how to best be of support to the movement and what I can do to actually be of use (not just performative or superficial). So, while my current body of work is actually on-the-nose timely, I’ve been holding back on sharing via social media because I don’t want it to come across in any way like capitalizing on the trauma of the moment. So, I’m still making the work but have been laying low a bit publicly in favor of using my social media to promote information about the protests.

Are you thinking differently? Coping differently? Inspired differently?

Initially in the pandemic I allowed my practice to free up a bit. My work is pretty tightly constructed / about heavy, dark subject matter, but I had been allowing a bit more levity to creep in. For example, I made a series of “Hex Hands,” small tufted rugs to ward off all ill will (coronavirus, patriarchy, white supremacy etc). In part, they reference a long line of protective symbols using hands— Azabache, Hamsa, Mano Cornuto— but they are also just a speculative, playful response to feelings of uncertainty and powerlessness (and they’re fuzzy!). But since the protests I feel like the moment of levity has been chucked out the window. I’m back to my regular way of working, with the only difference being that I have been catching up on a lot of reading that I had in the hopper but had not been making the time for.

Johannah Herr, Domestic Terrorism: War Rugs from America I (Immigration Detention), 2020. Machine-tufted rugs using wool, cotton and acrylic yarn. 4' x 6' x 1". Image courtesy of the artist.

What do you think or hope will be different after this crisis has passed?

In terms of the Black Lives Matter protests, of course I hope that the mainstream American psyche will be radically shifted towards social justice and antiracism. I hope that the work to be antiracist will be widely practiced in our schools, institutions, communities and families. I hope that this will be a turning point in our history that will forever change the trajectory of our nation for the better. In terms of COVID-19, I hope that mainstream Americans will have greater empathy for others who experience isolation, restricted movement, chronic fear and indefinite uncertainty on a regular basis— namely, those incarcerated in immigration detention centers, jails, refugee camps and those who are living as undocumented immigrants. Our experiences during quarantine are but a fraction of the trauma that these populations face on a daily basis, and it would be an amazing silver lining of the pandemic if everyone could have more empathy towards these groups.

Black womxn icon candles. Left to Right: Octavia Butler, Harriet Tubman, Marsha P. Johnson, Rosa Parks, Maya Angelou. Image courtesy of the artist.

Black womxn icon candles. Left to Right: Billie Holiday, Lorena Borjas, Ida B. Wells, Toni Morrison.

What is bringing you solace, or even joy, in this moment?

A few years back as Christmas presents for close friends I had made some colorful icon candles of featuring famous intersectional feminist scholars, activists and artists. I have recently remade / expanded the series of candles to 14 Black womxn icons and have been selling them as a fundraiser for BLM and other NGOs working towards antiracism. They are just small domestic objects but getting to share them with folx, raise money for the movement and remember these incredible womxn gives me a lot of joy. Also since COVID I find myself increasingly drawn to mailing people physical work— something about the tangibility and the act of gifting art gives me comfort and joy in these uncertain times. I feel like the resurgence of interest in making sourdough bread during quarantine (just look up #sourdough and you’ll see what I mean) comes from a similar place— a desire to return to making something with our hands, making something comforting and in a way, ancient. I started thinking about the connect between shared sourdough starters and the history of mail art— how sourdough starters can be infinitely generative, and how that might serve as an interesting metaphor and structure for a community art-making practice— and decided to start a project called @sourdough.starter_. The basic premise is that I mail artwork to other artists along with an ‘art starter’ of materials that I used to make the work. These artists then create new work incorporating the materials in the starter and send these new works on to other artists with an ‘art starter’ of materials that they used to make their new work… and so on. The instagram profile @sourdough.starter_ serves as a living archive of the project as these artworks spread exponentially out into the world. By including materials as an 'art starter,' I also hope the project can serve as small challenge to help artists create work that might be outside of our normal wheelhouses and connect our practices to one another's. It’s been going [since May 18th] and has already yielded some really amazing small works!

Black womxn icon candles. Left to Right: Audre Lorde, Sojourner Truth, Dorothy Height, Mary Bowser, Nina Simone. Image courtesy of the artist.

What research or writing are you doing that you find compelling?

I’m researching the history of design objects used by police / prison systems such as zip-tie handcuffs, body restraints and spit-guards, and revisiting some research I did years ago on propaganda textiles from the U.S., Soviet Union, and UK.

Johannah Herr, Domestic Terrorism: War Rugs from America III (Las Vegas Shooting), 2020. Machine-tufted rugs using wool, cotton and acrylic yarn. 4' x 2.5' x 1". Image courtesy of the artist.

Are you reading anything?

Reading / re-reading: Ibram X. Kendi’s How to Be An Antiracist, Susan Sontag’s Regarding the Pain of Others, Paul Morrison’s The Poetics of Fascism, Daniel Immerwahr’s How to Hide an Empire: A History of the Greater United States, and Greg Grandin’s The End of the Myth: From the Frontier to the Border Wall in the Mind of America.